Money from Sick People Part III: Why is U.S. drug pricing policy designed to exploit patients?

Our sickness Re-examined

Competition lies at the core of our healthcare infrastructure, touted as a fundamental element with vast market implications. It isn't just a buzzword. It’s a dynamic force that propels economic efficiency, fuels innovation, and elevates consumer welfare through a relentless push on the price of goods. This process translates into tangible benefits for consumers, as business rivalry results in better deals, discounts, and enhanced value for money. Crucially, competition is designed to act as a built-in watchdog, ensuring that market forces operate with precision – businesses face repercussions from consumers for overcharging, compelling them to recalibrate prices to align with consumer expectations or risk being undercut by the latest business start-up.

Despite the focus on competitive healthcare markets, a pervasive unease lingers among consumers regarding healthcare costs, hinting at a profound disconnect between their expectations and the effectiveness of the current system. We have ourselves dedicated years attempting to understand, through data visualizations and reports, the dynamics of drug pricing in the United States – often to be frustrated by the black box that envelops a drug’s price.

Through our series “Money from Sick People” (Part I; Part II), we have seen, time and again, a bothersome truth surface: consumers often find themselves relegated to the periphery of healthcare considerations, as rebates generated by sick patients are often taken and harvested by others.

Specifically, in our first Money from Sick People installment – where we examine the flow of dollars in traditional commercial pharmacy transactions – we found that with the popular insulin product Lantus, patients paid approximately $1,906.72 over the course of the year for a product that drugmakers received $828 for, while health insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) actually profit to the tune of $1,078.72. Under our second installment – where we examined the flow of dollars when transactions are subject to 340B obligations – we found that with another popular insulin product Humalog, patients paid approximately $1,802.52 over the course of the year for a product that drugmakers received $1.20 for and PBMs/health pay $1,493.88 for, while 340B covered entities receive $2,021.94 and their contract pharmacies receive $1,274.46.

This prompts a critical question: why are the purported benefits of drug discounts, whether in the form of purchase discounts or retrospective rebates, shrouded in an opaque cloak, hidden from the very individuals they aim to assist? If these discounts are genuinely advantageous, shouldn't transparency prevail? (thus allowing consumers to fully comprehend and leverage these benefits to the maximum extent possible). Digging deeper, the conundrum persists: why is it acceptable for over 60% of the product's value to remain obscured behind a veil of secrecy in a market that claims to prioritize consumer well-being?

Opponents of prescription price transparency staunchly argue that the confidentiality surrounding rebate and discount agreements is essential; deeming these negotiations as sacrosanct trade secrets crucial for maintaining a competitive edge. The rationale behind safeguarding these financial terms is the belief that by keeping such information confidential, negotiators can wield more influence and negotiate more effectively with various stakeholders in the drug channel without compromising their strategic position.

However, this seemingly pragmatic approach carries profound implications that extend beyond mere confidentiality. It embraces a troubling truth – the absence of a definitive, universally recognized “price” for prescription products. Instead, what emerges is a fluid landscape where all prices are inflated and contingent on negotiation, a delicate balance of leveraging positions and knowledge against one another.

This system, as exemplified by recent cybersecurity incidents like the Change Healthcare attack and the recent tragedy of Cole Schmidtknecht, reveals its inherent fragility. In a scenario where every price is subject to leverage, the intermediary becomes the gatekeeper, dictating the financial realities of healthcare costs on a case-by-case basis that they alone are privileged to understand. Said differently, “I cannot sell you this healthcare service as I do not know the price until I ask someone else.”

Can you imagine what it’d be like to shop at the grocery store if we had to consult Visa or Mastercard for every price in our cart? Further, can you imagine if the prices of products were not set in a traditional competitive manner but instead in an artificial reality where bloated sticker prices weren’t meant to accurately reflect anyone’s reality? This realization enables us to reflect on whether our healthcare system is inadvertently over-leveraged in terms of pricing and whether its intrinsic design entrenches intermediaries whose roles are predicated less on a tangible, meaningful service and more on the artificial value of providing relief from the environment of sky-high sticker prices that they helped create.

To be clear, this “over-leverage” doesn't conform to the conventional understanding of the term but underscores the reality that, in a system where all prices must be concealed to preserve negotiation leverage, the very concept of a stable, consistent, and transparent price becomes elusive.

The absence of pricing transparency in any market introduces significant flaws, impeding its efficient functionality. Without clear and accessible pricing information, healthy competition is compromised, leading to market inefficiencies. Information asymmetry arises, providing certain participants with advantages that are not afforded to others, allowing for exploitation and fraud. Distrust in the market ensues when participants perceive hidden or manipulated pricing information, negatively impacting transactions and the overall well-being of both consumers and businesses.

In a system that continuously feasts on high drug prices and high patient out-of-pocket costs as subsidies to provide value to others, the race to drug affordability will be a perpetual loser.

— Antonio Ciaccia (@A_Ciaccia) March 6, 2024

How Money from Sick People works: https://t.co/LcuVKJO2Jz pic.twitter.com/f5V9Ejxd1y

Does that not sound an awful lot like the complaints related to our healthcare system?

Which ultimately begs the question, why do we put up with this system, where the black box of drug pricing is intended to explicitly yield favoritism for some versus others, while leveraged discounts are withheld from the sick patients whose lives were pooled to create them in the first place?

Given our findings in how rebates work within traditional prescription drug transactions and how they work with front-end discounts through the 340B program, this seems like a question worth unpacking and answering. And while we cannot readily provide all the answers, we can offer some perspectives based on our years of studying drug prices, as exemplified through our Money from Sick People series, and the policies that govern them.

For the sake of clarity, we’re offering these perspectives of different stakeholders in the prescription drug transaction from the point of view as if insulin was the only drug available in the marketplace. Obviously this is not the case, but insulin is the drug which offers us the greatest transparency into the inner workings of the brand drug rebate system; so we’re assuming that insulin is demonstrative of the issue at large (and therefore assume insulin is the only drug that matters for the purposes of these perspectives; the implications for other drugs will range in terms of severity). Before reading on, please ensure that you have read our prior “Money From Sick People” (Part I; Part II) series, as they will be heavily referenced within these perspectives.

Speculating on why we put up with sick patients overpaying for medicines to provide value to others

Drug manufacturer perspective

To start, one wonders why drug manufacturers endure such a system, where so much of the value of their medicines gets lost in the plumbing of the drug channel without the full value of their offered discounts being passed on to the end payer – the healthcare consumer. Time and again pharmaceutical companies have made clear that one of their principle business interests is market share – which in this case is understood simply as people taking their drug. In order to take their drug, consumers must be able to afford their drug, which with the high prices of brand medications, requires that most of them get assistance from health insurers and their PBMs to do so.

That process of getting consumers to buy their drugs has a lot more gatekeepers to its activity than most other business transactions.

First, regulatory bodies such as the Food and Drug Administration require extensive pre-market evidence that their marketed product is safe and effective for use within our healthcare system. Try to think of other consumer goods that face such pre-market hurdles – there aren’t that many (and to be clear, this isn’t a horrible thing; we need to know medicine is safe and effective before taking it).

Second, the access to consumers requires doctors and other prescribers – some of the most educated members of our society – to value the treatment above alternatives and provide an order for use to the consumer such that the drug can be taken. As a result, convincing doctors to prescribe their product is the next hurdle to gaining the market share that a drug manufacturer’s business is so dependent upon.

Immediately after convincing the prescriber to write the prescription, the dispenser must be convinced to stock and sell the medication to the customer. Regulations place a corresponding responsibility on the pharmacist to ensure safe and effective prescribing. Pharmacists must use professional judgment when making a determination about the legitimacy of a prescription. A pharmacist shall not dispense a prescription of doubtful, questionable, or suspicious origin and so yet another highly educated member of society seeks to protect the patient even after the prescriber has been convinced to write the prescription. If pharmacists don’t carry the drug because they deem it of low value, or won’t give it to the individual patient due to a lack of benefit for them, then the drug still will not reach the end consumer. However, the story doesn’t end with FDA, prescriber and pharmacist oversight.

Next, there is the reality that an overwhelming majority of prescriptions are covered via third-party payment typically facilitated through health insurers and their PBMs. This is especially true for brand-name drugs, where medicines are priced as the starting point for discounting rather than to sell “as is.” In this world, drug companies face formulary and other utilization controls imposed by PBMs and health plans that significantly impact the market share sought by the manufacturer. Ostensibly, prior authorization requirements serve as a double-check to the decisions of the prescriber to ensure that the medications paid for by the health plan are safe, effective, and available at a reasonable cost. However, as a consequence of changes to anti-kickback laws in the late 1980s / 1990s, the current practice of brand drug manufacturers is to provide retrospective rebates to plan sponsors and their contracted PBMs to ease restrictions to their therapies and make it easier for consumers to get insurers to help pay for the drug. Said differently, drug manufacturers pay for access to consumers through discounts provided to the consumers health plan. And this would be viewed as a kickback but for the law specifically exempting this type of activity from being designated as such.

Figure 1

Source: Drug Channels Institute

According to this excellent deep-dive from Foley Hoag on the history of drug rebates, before these changes to federal anti-kickback laws, “most manufacturers offered either upfront discounts on their products in exchange for greater volume and formulary access or else rebates not conditioned on volume – much like the type of upfront pricing.” That type of discount activity mirrors what consumers are used to for other goods. While the history of the “before times” and its immediate aftermath are fascinating, the end result is that the giant $300 billion pot of rebate stew has become the primary vehicle in which manufacturers and purchasers negotiate discounts on drugs. As way of proof, consider that for much of the overall value of drug spending (i.e., greater than 50% list price reduction) potentially available via this drug rebate. Can you think of other forms of consumer spending where our expectations are effectively half off the price of every transaction? We cannot.

Such negotiation can ultimately lead to big disconnects between “the price” of a drug depending upon your place within the drug supply chain. In the aggregate, we know that purchasers for brand drugs may get discounts ranging from nearly nothing (i.e., no rebates) to almost free drugs (i.e., 90%+ of the cost being rebated). Such a range of price is hard to comprehend, but we know from investigations into insulin pricing that prices can be effectively half off most of the time – and in some instances, like with 340B providers, effectively 100% off the typical market price.

So why do brand drug manufacturers put up with such a system, especially as they continue to receive an overwhelming majority of the blame for high drug prices but about half the actual yield from the prices they set?

Perhaps the quickest answer is that they don’t want to put up with it, as recognized by their recent lawsuits related to 340B contract pharmacies or lawsuits related to IRA price negotiation provisions. However, those lawsuits notwithstanding, they have an easy (albeit, impractical) way out of the 340B and rebate paradigm. If drug manufacturers opted not to sign the National Drug Rebate Agreement (NDRA) with the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), then they do not have to offer Medicaid a rebate for their drugs, nor do they have to sell their drugs at 340B prices to Covered Entities (no obligation to sign the pharmaceutical pricing agreement [PPA] that governs 340B pricing). Similarly, they could choose not to sign rebate agreements in the private market (good luck there). From the point of view of the manufacturer, it seems that the problem of their discounts not reaching consumers would be solved through these actions and drug manufacturers make even more money, right?

While this approach is undoubtedly simple and seemingly straightforward, it is likely not a practical business solution for most manufacturers. Consider that Medicaid enrollment was roughly 87 million people at the end of 2023 (roughly one quarter of the entire U.S. population). With those kind of numbers, it is very apparent that manufacturers would be missing out on large swath of the patient population by not signing a NDRA (to say nothing of the roughly half of all hospitals and pharmacies who may be less inclined to stock your drug if you’re not also participating in the 340B program via the PPA). At the same time, the rest of the market (i.e., commercial insurance) likely looks at the statutory discounts Medicaid is getting (have you see those MACPAC figures we’ve previously reported on where brand drugs in the aggregate are effectively discounted 60%?), and make demands for rebates for themselves as well. Said differently, would you be comfortable paying full price for something you knew your neighbor bought for half off?

However, we do not feel that is the entire story either.

If drug manufacturers are going to give rebates to everyone as a result of having to give them to Medicaid and 340B, why don’t they seek to equalize the rebate across the board? Said differently, inherent within the concept of a “best price” rebate is the other side of the spectrum: the worst price. While manufacturers may be constrained by those they must give “best prices” to, meanwhile there are other purchasers who are going to pay a lot more (even after rebates or discounts) for the same drug. Other countries have more uniform drug pricing experiences through more rigid government programs, negotiations, or price controls, so why don’t manufacturers advocate for (rather than oppose) those programs here? We think the answer to that question is as simple as looking at their incentives, and we think we can do so with insulin (our proverbial punching bag of drug pricing dysfunction), but first we need a few pieces of background information to make our point.

In 2021, Drug Channels Institute estimated the gross-to-net bubble in the United States to be worth $204 billion for brand-name drugs. At the same time, we know the size of 340B discounts purchased was $43.9 billion and Medicaid rebates were worth $42.5 billion. Proportionally, this means that roughly 42% of all brand-name discounts (i.e., $43.9 billion + $42.5 billion divided by the $204 billion total) were associated with these two programs alone, with the rest remaining for everyone else. If we conceptualize that in relation to Humalog prices, we think we gain valuable insights into why manufacturers might agree to this program in the first place. Diabetes is a common enough drug that it likely equally spreads its discounts across the market fairly proportionally to these overall figures.

Figure 2

Source: Eli Lilly & Co.

Recall from last week’s Money from Sick People analysis that the net price for Humalog in 2021 was estimated at $87.90 for commercial insurance, whereas Medicaid/340B got the drug for $0.10. Based upon these data points, we’d say that the effective net price for the entirety of the U.S. market in 2021 likely approximated $50.71 (44% of the market getting insulin for $0.10 [the amount of Medicaid and 340B influence], with the rest getting it for $87.90). This approximates what Eli Lilly told us their net insulin price per vial was in their 2019 Integrated Summary Report (Figure 2), which we feel at least semi-validates our methods since we’re using one rebate price for commercial when we really know multiple prices exist.

Interestingly, this estimated net price for the U.S. market is in-line with our understood net price of Humalog that we would get from the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS), which listed Humalog’s price as $51.77. (as a reminder, FSS is supposed to be a proxy for best commercial net prices, further validation in our mind of where the market is; this price covers the 2019 to 2021 timeframe based upon contract date). Additionally, that price isn’t far from what we believe international prices for Humalog were at roughly the same time. A vial of Humalog was roughly $44 in Canada in 2020 or $55 in Germany in 2019.

But unlike those international programs where $50 is the “universal” price in their respective programs, the differentiation of price in the U.S. market gives the manufacturer “upside” opportunity. As times get better (economically), less people are going to be enrolled in Medicaid (where enrollment for a large portion is determined in part by their income); therefore, less people will get the “best price.” As less people get the best price, the upside for the manufacturer exists for the U.S. in ways that don’t occur in other markets. Consider what happens if we roll forward our proportionality to the numbers based upon 2022 data (leaving the Humalog net prices alone). In 2022, the total gross-to-net bubble from Drug Channels was estimated to be $300 billion; whereas the 340B program was estimated to be $54 billion and the Medicaid rebates were estimated to be $48.5 billion. Under this proportionality, Medicaid and the 340B program are now 34% of the market (whereas previously, they were 42%). Keeping our Humalog list prices unchanged into 2022 means that now, the collective insulin net price is $57.90 (34% of the market at $0.10 net price; 66% of the market at $87.90 net price). As a consequence of “best price” program contraction, the net Humalog price for the manufacturer improved (without factoring in changes in other market conditions).

This, in our opinion, is a perspective often missing from the dialogue regarding net price motivations. In international markets, the only way for the manufacturer to improve their financial picture is though universal price improvement (i.e., all prices within the country’s market going up; a challenging feat). In our opinion, convincing millions in these countries to pay more for their drug costs doesn’t seem likely to succeed.

In the United States, the best price vs. worst price paradigm creates upside opportunity (with downside risk) that doesn’t exist elsewhere. As economic times improve, manufacturers stand to make more money through less sales made at the ‘best price’ (less enrolled in Medicaid). And in times when there are economic challenges (and more people end up enrolled in Medicaid), manufacturers can preserve access to their therapies through sweetheart deals to the government payer (i.e., Medicaid). And so, perhaps that is why the manufacturers are generally not advocating for equalizing price in the U.S.

As former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb opined back in 2016 during the Mylan Epi-Pen saga, “The convoluted arrangement by which drugs are priced and sold arose accidentally as a result of litigation. But now that this inept system is firmly entrenched, bringing rationality to the selling model is going to disrupt inter-reliant business practices. As much as the drug makers complain about the rebating scheme, they’ve grown as dependent on its subterfuge, opacity and inequity as everyone else in the system.”

This in turn raises the question, why does the government put up with this system of haves and have nots (best prices and worsts)?

Government perspective

The government has become a dominant payer in the healthcare space. Besides the 87 million lives enrolled in Medicaid, the government is also helping to pay for the drugs of 66 million enrolled in Medicare. Collectively, these two programs represent roughly 40% of all U.S. lives (and therefore an approximate 40% of the healthcare market). However, they have very different drug price experiences. We know from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), no one gets a better drug price than Medicaid. Across the federal programs of Medicaid, the VA, Federal Supply Schedule, and Medicare, Medicaid is the best and Medicare is the worse (in terms of net drug price; see Figure 3):

Figure 3

Source: Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

In looking at the above, what Medicare spends $100 on in the net, the Federal Supply Schedule will buy for $93 (a proxy for the commercial market), the VA will buy for $55, and Medicaid will buy for $35. Why put up with the differences? Well, in our opinion, the differences make it easier to finance the program whose drug costs on paper are most reliant on federal dollars (general revenues).

In Medicaid, patients generally do not pay premiums or generally share in any meaningful amount of drug costs (copayments are generally capped at $8, with many patients paying nothing at all in out-of-pocket expenditures). Having best price protections for a subset of that federally-funded drug market makes the financing of those benefits far cheaper for the U.S. government than it might otherwise be. Outside of the inability to cost-shift onto patients in the Medicaid program, Medicaid financing includes a promise from the federal government that no less than half the costs of the program will be borne by the federal government. In many states, it’s more than 50% (half is the statutory minimum). The maximum possible match is 83%, and today, Mississippi is the state with the highest match at 76.9%. With so many federal dollars at stake, it makes sense why the government might want the benefit of “best price” for this program.

Consider a model where everyone in the U.S. got the same net insulin cost of around $50 (a la international pricing). Medicaid would go from spending $0.10 per vial (via their current best price position) of Humalog to $50. This would make servicing insulin 500-fold more expensive for Medicaid. To be more specific (while doing back-of-the-napkin-style math), there were a total of 560,000 prescriptions for Humalog in Medicaid in 2021. If each of those prescriptions were $50 more expensive in the net, then added costs for Medicaid would have been $28 million annually (and that number is likely underestimated since the State Drug Utilization Data which we’re relying upon to count Humalog prescriptions excludes 340B). No way around it – that’s a lot of money.

In Medicare, drug costs are shared via a variety of sources, including premiums paid by beneficiaries, beneficiary deductibles, direct subsidies provided by the Federal government, and retrospective price concessions (i.e. rebates) recognized as direct and indirect remuneration (DIR). Prescription drugs in Medicare are sourced through the private market, with rebates between Medicare and commercial being roughly equal (average Medicare rebate percentage of 28% compared to median commercial rebate of 22%; both in 2019).

However, we know that rebates generally make drugs more expensive for individuals (hence Money from Sick People). For example, the government acknowledged that pharmacy DIR was increasing patient drug costs in Medicare; therefore, it stands to reason that drug manufacturer DIR is also increasing patient drug costs (to the extent that a particular plan is not using it to lower patient cost sharing; not all plans are equal).

Again, some back-of-the-napkin math: In Medicare in 2021, there were 648,000 prescriptions for Humalog. If each of those prescriptions was $37 cheaper in the net (estimated $88 in the net today to a $51 estimated equity net), Medicare would have saved $23.9 million. While a good chunk of change, recall our earlier number for Medicaid added costs was higher, meaning it’s a net loss to the government to equalize net drug costs across these two programs (to say nothing of the differences in how programs are actually financed and where the added costs would be recognized).

All of this is to say, Money from Sick People works in the interest of the government financing the bill. In the program where government dollars dominate payment for prescription drugs (i.e., Medicaid without patient premiums or cost share), the “best price” rules determine drug costs. In the program where costs can be shifted onto patients, Medicare used Money from Sick People to do just that (money made on one person’s drug purchase can make another person’s healthcare services and/or insurance premiums cheaper).

Looking back again to former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb’s comments from 2016 about the prospect of eliminating rebates, he stated, “Government payers like Medicaid would also resist such a change. The government uses the rebates as a way to re-allocate healthcare dollars to other projects, while being able to still claim that their reported pharmacy budget is rising by ridiculous amounts.”

And of course, remember, whenever someone gets the best price, everyone else gets a worse price. Government-mandated price concessions for their own growing programs creates upward pressure on the list prices that plan sponsors and patients are left to grapple with on their own.

And this phenomenon only seems to be expanding. With Medicare moving into creating their own price negotiations and special rebates under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Biden administration already seeking to expand those efforts, more of the marketplace will be shaped by federal policies governing rebating requirements. Further, as we highlighted last week, the rapid growth and expansion of the 340B program demonstrates further extrapolation of the “best price” obligations imposed on manufacturers. With these dynamics in mind, the impact of government-mandated deals on distorting the rest of the market may only grow in the years to come.

So when it comes to the government, it’s good to be the king.

This in turn raises the question, why do businesses put up with the government exposing them to the ‘worst’ prices?

Health plan and PBM perspective

We have already covered why health plans and PBMs prefer Money from Sick People in our previous Money from Sick People installments (both Part I and Part II). As we demonstrated, the ability to profit off someone’s drug therapy is pretty much unique to any form of insurance anywhere else. Health plans generally use rebates to make their premiums look more competitive than they would otherwise be. Said differently, in a world without rebates (and instead having up-front discounts), it stands to reason that a stand-alone drug plan would be cheaper than a drug plan as they exist today. However, the cost of doctor and hospital insurance would likely be more (drug rebates can be used to make medical insurance seem more affordable – when it’s all rolled into one health plan).

While the ability to profit off drug rebates and create more attractive member premiums are obvious incentives for health plans to favor a rebate-driven system, their preferences may not appear so cut and dry when it comes to things like the 340B program, particularly given that health plans (including their plan sponsors) don’t get the rebates on those 340B-eligible claims (see rebate contract exemptions between health plans and PBMs).

We believe that the health plans and PBMs put up with the 340B program largely because it is viewed as part of the cost of doing business. Sure, they would like to still get their rebates on claims dispensed through the 340B program (and maybe they do sometimes when duplicate discounts occur), but even assuming all programs are working perfectly, we can see why health plans might tolerate the 340B program. Again, we’ll use proportionality to demonstrate.

In 2021, Drug Channels Institute (who also has some interesting perspectives on PBM profit opportunities in 340B) previously identified $204 billion in brand-name gross-to-net bubble spending – $43.9 billion related to 340B drug purchases and $42.5 billion related to Medicaid. If we remove the role of Medicaid from this, we would say that roughly 1-in-4 of the gross-to-net bubble dollars are captured by 340B ($43.9 billion out of $161.5 billion [$204 billion total minus $42.5 billion Medicaid]). As an aside, our methods in this regard produce similar sizing to the different methods employed by IQVIA in their recently published model on 340B impacts to commercial payers.

In last week’s Money from Sick People Humalog report, we showed that health plan costs are -$747.67 for Humalog annually per patient when they collect a rebate and +$1,493.88 when the 340B Covered Entity captures the discount. So while under traditional pharmacy transactions, health plans and PBMs capture the value of rebates, when those claims are subject to 340B discounts, those rebate dollars are forfeited to covered entities and contract pharmacies.

Well, if 3 out of 4 times, a health plan can make $747.67, and 1 out of 4 times, a health plan loses $1,493.88, their net experience is still positive to the tune of $749.13, ergo it is cheaper to have this model continue than to advocate for a model where all net prices are the same or where 340B providers were not entitled to their discounts. Said differently, if 340B providers giving up their discounts would also require health plans to give up their rebates, that math doesn’t seem in their business interests (though there are cash flow implications to waiting to recognize discounts retrospectively; while that is a conversation for another day, we should recognize that the carrying costs of rebates was a lot lower when interest rates were lower and so maybe some of this math warrants revisiting by plan sponsors).

Again, the Money from Sick People perspective is creating more opportunities to win than lose, and so the system is preferred to the alternative. Recall in our past studies, we saw that if we move any of the discounts in the system up front – even if the health plan never incurs a cost due to the patient never reaching their deductible – the health plan is losing out on the money it is currently making (and therefore $0 is a higher cost to the plan).

As we have said before, we should trust businesses to follow their incentives, and perhaps this can help explain why many plan sponsors, insurers, and PBMs have thus far mostly sat on the sidelines of advocating for changes to the rebate system.

Wholesaler perspective

Figure 4

Source: United States Senate Finance Committee

They can’t all be winners, right? Surely if everyone else doing the “selling” of products (drug companies, insurance companies), then those next in the drug supply chain stream must be losing right?

On its surface, the answer appears that yes, drug wholesalers may stand to lose from this system since, at least according to Eli Lilly’s own internal communications (Figure 4), they may be able to pass on higher costs to wholesalers if most of the big health plans prefer their drugs.

However, this is not likely the full picture in the wholesaler’s mind. To start, the email in Figure 4 also signals that wholesalers are getting rebates/discounts/fees from drug manufacturers as well, so maybe they think of the traditional rebate system just fine the way it is.

But what about 340B? What role could 340B play for the wholesalers and how might understanding that role help broaden our understanding of why this system may be in the interest of wholesalers?

As a first point of consideration, we look to the Healthcare Distribution Alliance (HDA), the trade association representing wholesalers. They published a report in 2019 examining the 340B program and its impact on market participants. While there aren’t any obvious tells, we find a few pieces of information worth closer inspection.

First, the report makes plain the obvious that 340B Covered Entities are entitled to buy drugs cheaply, stating “savings between 15 and 50 percent of the average wholesale price for covered outpatient drugs.“ In general, 340B providers are making these purchases not directly from manufacturers but through wholesalers, which, it stands to reason, eats away at the wholesaler’s bottom line (they have to sell these products cheaper than they otherwise would, making the wholesaler less money). However, the report makes a key point of what those 340B purchases enable 340B providers to do: buy up other providers’ practices. As stated in the report:

“A 340B hospital can purchase these drugs at the discounted 340B price, while a non-340B entity cannot. Both entities are reimbursed at the same rate, so the 340B hospital yields a greater profit. These discounts create greater than market financial incentives for 340B hospitals to administer 340B drugs, particularly for expensive injected and infused drugs. These incentives are a contributing factor to the trend in hospital acquisitions of independent physician offices.”

In addition, the report goes on to state that the growth of the 340B program has likely contributed to manufacturers increasing the launch price of new therapies. Again, as stated in the report:

“As prices increase, 340B and other government program prices remain anchored by statutory indexes to inflation. As such, net sales and profitability for manufacturers decline, and this can place upward price pressure on commercial drug prices (in the form of higher list prices or lower discounts to commercial purchasers). When new drugs are introduced, they may be priced higher to factor in the statutory discounts and the growth of the 340B program, Medicaid and other government programs to ensure that profitability targets are met.“

We take the above two sections to mean that wholesalers are concerned that 340B poses risks to their customer base (as more providers are associated with the 340B program, there are less whom they can make “traditional” sales to), while at the same time increasing the potential carrying costs of their inventory (if drugs are coming to market at higher costs, the carrying costs wholesalers incur between the time they buy the product from the manufacturer and the time they can sell it to their customer potentially increase). However, we’re not sure it is all bad news for the wholesalers in regards to money from sick people.

While it is true that wholesalers are generally obliged to sell the products to their customers at the 340B price (based upon the Covered Entity being on the list of eligible entities maintained by HRSA) – which would undercut the margin they might otherwise sell the drug for (if they were a traditional pharmacy purchaser) – wholesalers have found ways to profit off the 340B program too.

Each of the major wholesalers acknowledge the 340B programs within their 10-K filings, as they are able to earn additional revenue for their role in the 340B program. They do this through offering proprietary inventory management software and consulting services to help Covered Entities with program compliance. Prescription technology services are a growing portion of the revenue streams for many of the large U.S. wholesalers. However, such segments are still small parts of the wholesaler operation relative to their traditional role of wholesaling drugs to customers (see McKesson reported revenues by segment in Figure 5:

Figure 5

Source: McKesson 10-K (2023)

Therefore, the value of 340B to wholesalers might have less to do with selling the 340B technology services they offer, and more to do with the general pain of wholesaling traditional drugs to traditional customers. 340B Covered Entities are generally prohibited from obtaining covered outpatient drugs through a group purchasing organization (GPO) [not all Covered Entities, specifically disproportionate share hospitals (DSH), children’s hospitals (PED), and free-standing cancer hospitals (CAN); additionally, hospitals subject to the GPO prohibition can use a GPO for purchases that do not meet the definition of a covered outpatient drug].

Ultimately, there may be value to wholesalers through reduced GPO participation, considering that they generally acknowledge that GPOs are impediments to their profitability within those same 10-K statements. As McKesson notes, their top 10 customers account for 68% of their sales and, “Many of our customers, including healthcare organizations, have consolidated or joined group purchasing organizations and have greater power to negotiate favorable prices. Consolidation by our customers, suppliers, and competitors might reduce the number of market participants and give the remaining enterprises greater bargaining power, which might lead to erosion in our profit margin.“ (our own emphasis added)

So, while wholesalers may experience some winners and losers among traditionally rebated drugs, the 340B program may be a bit a mixed bag as well. But since wholesalers in general make money as a percentage off the list price of brand drugs, the pressure that rebates put on inflating the list prices of drugs may prove to be their most beneficial feature (i.e., 3% margin of $1,000 drug is more money than 3% of a $100 drug).

So all things considered, wholesalers may favor the broader rebate-based system as it is in that it allows them to potentially differentiate customer costs in ways advantageous to their bottom line, skirting near and around Robinson-Patman Act, in a manner similar to what we highlighted with manufacturers above.

Pharmacy perspective

So if health plans, the government, wholesalers, and even the drug manufacturer can find wins via this system of best and worst prices, where does that leave pharmacies?

As we already observed with the wholesalers, pharmacies may face increased costs for drugs if wholesaler rebates for drugs drop off. However, we’re not sure that pharmacy universally loses via the rebate system either – so long as they get to play in the 340B space.

Recall that the 340B program and the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program are inherently linked, meaning that the best prices extended to Medicaid programs are extended to Covered Entities, which have their own in-house pharmacies where they are intended to take the drugs they acquire for those low prices and then sell at high mark-ups. As reviewed in last week’s report, those Covered Entities can expand their reach for 340B spreads by engaging networks of contract pharmacies who work to cultivate more 340B-eligible claims through an expanded market footprint.

As can be seen in Figure 6, the splitting of 340B assets between Covered Entity and the contract pharmacy can be lucrative for both parties. In the Humalog example, we see a drugmaker selling the drug for a total return of $1.20 over the course of the year, the patient paying $1,802.52 and the health plan/PBM paying $1,493.88 for those claims. Meanwhile, the Covered Entity takes in $2,021.94 and the contract pharmacy takes in $1,274.46.

While the Covered Entity is expected to invest these added resources in uncompensated or undercompensated care (and there is recognizable value when they do), there is controversy to the degree with which all those revenues are actually being used to meet those ends. Without weighing in on that debate, it’s important to understand that when 340B revenues are not fully invested in their intended ways, the margins become key marketplace differentiators for those harvesting those spreads.

Back to Humalog, the data suggests that for non-340B claims, traditional pharmacies barely break-even when dispensing the drug to patients. In our studies of the pharmacy market over the years, that Humalog experience isn’t an anomaly. Brand drugs are typically low-margin opportunities at best for pharmacies, with many instances of pharmacies being paid below cost form PBMs working on behalf of health insurers. That’s very different than the 340B experience, where those same pharmacies can make over $100 per prescription.

Figure 7

Source: 3 Axis Advisors

But Humalog is just one drug. How about all brand drugs? Through our team’s consulting work at 3 Axis Advisors, in an analysis of pharmacy reimbursement trends in Oregon, we see that among retail pharmacy study participants from 2019 to 2021, pharmacies saw an average reimbursement of $3.38 above the underlying cost of brand drugs (as quantified by national average drug acquisition cost), which is still profitable, but well below the $10 or so that a pharmacy needs to break even on their overhead costs. Our own 46brooklyn Medicaid Dashboards show Humalog is a product associated with anywhere from a $5 loss per unit to a $1.47 margin above cost per unit in Q3 2023 (hardly a winner).

In case the theme of these perspectives isn’t obvious at this point, as we move onto why pharmacies put up with this system, it is again a matter of opportunity cost relative to the status quo. The contract pharmacies who have the opportunity to make around $100 dollars in margin per prescription in 340B have the potential to off-set a lot of losses. If pharmacies were actually losing $10 per prescription of Humalog in normal circumstances – or even making $3.38 in margin per brand prescription as a whole – the $100+ in profit per prescription through 340B completely changes the economic picture for those pharmacies by wiping out the impact of the meager PBM reimbursements on brand drugs and turning an adverse financial picture into a far more lucrative one.

So even though our previous data suggests Humalog is likely an underwater or at best, a break-even experience for the pharmacy in terms of just the cost of the drug, even if we assumed that pharmacies made $3.38 in margin per Humalog prescription filled through conventional means, for 340B contract pharmacies, the estimated profits of $106.21 per prescription would be a profitability swing of more then 3,000%. So, great money if you can get it. This is especially true if you consider that contract pharmacies aren’t required to use the yielded returns for undercompensated or uncompensated care, as 340B spreads are supposed to be used for. Note: however, in our experience, we are well aware of pervasive underpayment issues that exist for community pharmacies – we know of many community pharmacies that likely would not exist if not for the value provided from contract pharmacy engagement – so perhaps from a certain point of view, 340B mission fulfilled (via “expanding” access that otherwise would have shut down).

And speaking of pharmacy underpayments, some more recently unearthed PBM contracts paint a rather dire situation for community pharmacies. As just a sampling of some of the public-facing reimbursement terms, the Community Oncology Alliance references drug payments clipping as low as AWP - 24.5% and zero dispensing fee for 30-day supplies of brands, a popular anonymous pharmacist on Twitter showing rates as low as AWP - 25.5% and zero dispensing fees for 30-day supplies of brands, and the incomparable Matt Stoller revealing network rates as low as AWP - 26.3% and zero dispensing fees for 30-day supplies of brands.

Make no mistake, those contracts paint a dire picture of brand drug reimbursement for community pharmacies. That’s not an opinion; it’s reality. Here’s why.

We know from our understanding of drug reference prices that such reimbursement rates are likely to put the pharmacy in no position to be able to actually fill these brand prescriptions above or even at their acquisition cost (to say nothing of positioning their business to make a profit). To demonstrate, consider what we know from national average drug acquisition cost (NADAC) regarding the typical brand acquisition cost relative to average wholesale price (AWP) (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Source: NADAC Equivalency Metrics at Medicaid.gov

According to the NADAC equivalency metrics published quarterly, brand drug acquisition costs for retail pharmacies approximate around 20% discount to AWP. This is the same quarter-after-quarter. There is almost no difference between the mean and median, suggesting a pretty uniform relationship across the various brand products surveyed. For those of you familiar with AWP, this relationship between brand drug acquisition costs and AWP is not surprising. Numerous lawsuits in the early to mid 2000s established precedent that effectively mandated this relationship for brand costs.

So if a hypothetical brand drug had an AWP sticker price of $1,000, this data from CMS suggests that retail pharmacies would likely pay $800 for that drug. The worst-case scenario contract referenced above (AWP - 26.3% and no dispensing fee) would mean that pharmacies would only receive $737 for that drug – an significant loss of $63 for the retail pharmacy dispensing the drug to their patient.

We can only speculate, but given that effectively half of all pharmacies are playing in the 340B space (via contract relationships with Covered Entities), it seems that these terms are seeking to extract some of the discount purchases out of the system. Recall that many states have enacted legislation that prohibits PBMs from disparaging 340B-related claims from a reimbursement standpoint – the rationale being that PBMs shouldn’t be the ones recognizing the value that “best-priced” drugs are supposed to create.

But regardless of whether a state has passed these laws or not, given the growth of the program, they may not matter. If over half of pharmacies are harvesting the added margins and value from the 340B program, PBMs likely understand that the excessive pressures on brand-drug reimbursements will be tolerated by a majority of their network. From the PBM perspective, if you cannot specifically target 340B claims for differentiated payment terms relative to non-340B-involved pharmacies, then it stands to reason that the response would be to try to collectively extract the value out of the system writ-large. As we stated at the outset, drug pricing in the United States is a highly-leveraged pricing environment.

This in turns brings us back to our earlier point as it relates to establishing drug prices through leverage. A leverage contract is not necessarily one that gets any individual transaction pricing “correct.” Consider an accounting exercise where you buy one, get one free (who doesn’t love a BOGO?). In the aggregate, we understand what we pay when buying two products via a BOGO sale. But from a line-item view, do we recognize costs as 100% for the first purchase and $0 for the second OR do we line-item a 50% discount for each purchase? While the issue may not matter in the aggregate, it certainly matters for the individual purchases, which in our case, are individual consumers buying drugs. Which can leave some questioning – who actually got the value of the BOGO discount?

We feel this approach to fully leverage drug prices via aggregate discounts helps explain why some people can say buying insulin (for example) is affordable while others say insulin costs are unaffordable. Their purchases are being aggregated in a collection that doesn’t necessarily concern itself with getting any individual transactional prices correct. And that may not work well for individual consumers (or at the very least, it may make them feel like they’re getting short-changed on drug prices).

The issue manifests itself through disparity; most readily recognized for pharmacies trying to purchase inventory and ultimately compete for customers. A pharmacy not plugged into the 340B system – whether as a covered entity or a contract pharmacy – is at a massive competitive disadvantage to its peers. When much of the 340B contract relationships are tied up in PBM-affiliated pharmacies or large pharmacy chains (who can command larger referral fees and spreads than their smaller and less favored competitors), the rest of the pharmacy market can be squeezed out pretty quickly. Said differently, a majority of pharmacy operating costs are tied up in the carrying costs of brand-name drugs – unless they aren’t because you’re getting brand-name drugs for close to free (or quite literally free through virtual inventory replenishment).

Thus you will often find many pharmacists and pharmacies that do nothing but sing 340B’s praises, recognizing that it gives them rare access to the slice of “best prices” and “best margins” that other pharmacies may never experience. Whereas most of the traditional pharmacies – who are faced with the adverse economics associated with buying expensive brand drugs from wholesalers at bloated sticker prices and getting reimbursed at or below their acquisition costs by PBMs – are wondering why anyone would even want to dispense brand drugs (heck, some have already stopped stocking brands altogether), other more fortunately situated pharmacies are wondering how they can get their hands on even more.

While this distorted and disparate reality for pharmacies suggests that PBMs may be finding value beyond traditional rebating and the yields from being contract pharmacies for some of the most lucrative drugs in the marketplace (by capturing more 340B value by underpaying for brand drugs dispensed by participating pharmacy providers), this certainly points to an uncomfortable civil war brewing among the pharmacy community, where 340B is creating winners and losers among competitors.

Will pharmacy organizations advocate for better parity among its market participants or turn a blind eye to the obvious inequity?

To be clear, issues of haves and have nots will likely always exist in all marketplaces, but when one pharmacy loses money for the same drug that a competitor yields $1,274.76 for, the spectrum of haves and have nots is less of a game of inches and instead a game of parsecs. And since this isn’t a phenomenon borne out traditional competitive dynamics, but instead a government program creating the disparity, the sting of the inequity during harsh economic conditions for community pharmacies hits all that much more.

Patient perspective

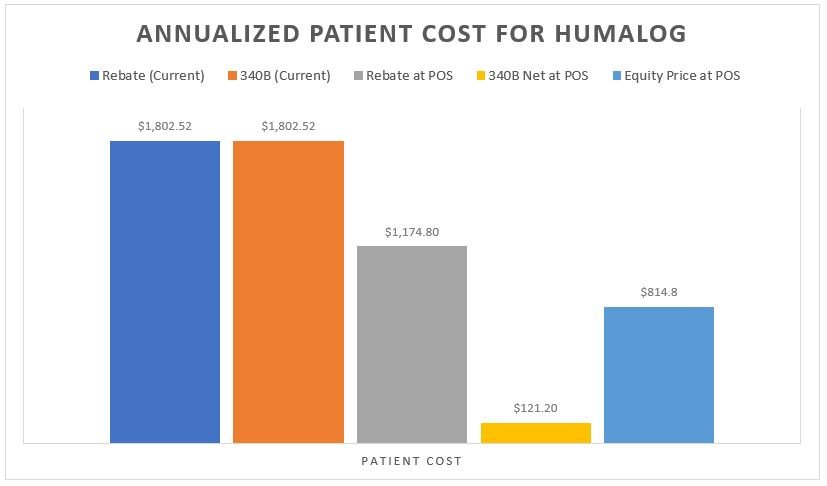

As with with any analysis that deals with prescription drug rebates or discounts, last and least is always the patient. To recall from our earlier analysis on the matter, we find it noteworthy that any model that would seek to recognize the net value of the prescription at the point-of-sale is an improvement for the patient. Whether it is the model where the insurer doesn’t take the rebate (i.e., $87 up front) or the Covered Entity doesn’t overcharge relative to their acquisition cost (i.e. $10.10 charge to the patient), patients would pay far less for their Humalog than they do today (see Figure 3 Patient Cost Column [B] for current experience relative to the same column in Figures 9 & 10 in our prior report). Similarly, if we imagined a world where everyone was getting access to the same net price (i.e., an equity-driven model where all payers are charged the net price of $51), the patients (collectively) are would again be paying less (Figure 9 below).

Figure 9

Source: 46brooklyn Research

Putting all the various scenarios we’ve generated on this topic, side-by-side from the patient’s perspective on Humalog, it shows perhaps why so many people were struggling with their insulin costs and rationing their insulin (despite low net costs available in the system today [either from the health insurance company or the 340B Covered Entity perspective]).

Figure 10

Source: 46brooklyn Research, Column B from Figures 3, 4, 9, 10, & 16, Money From Sick People Part II

Ultimately, we feel Figure 10 speaks to the inherent misalignment of drug pricing today in ways that perhaps nothing else we’ve discussed today really can. Figure 10 underscores the variety of possible patient experiences available within the U.S. today; in ways not all that different from the “best” and “worst” scenarios observed across various perspectives within the drug supply chain before patients (that we highlighted above). While our analysis centers around averages – average deductible, cost share, and cost per vial – we acknowledge that these averages don't encapsulate the full spectrum of experiences. Some health plans leverage rebate dollars to minimize cost sharing, such as Medicaid with minimal to no cost sharing, and certain private plans follow suit. Additionally, certain patients gain access to reduced drug prices and other healthcare services through programs like the 340B price via Covered Entity charity care, offering crucial support to those otherwise unable to afford treatment.

For individuals benefiting from these avenues of assistance, the system works (or we suspect they’d offer a perspective that the system is working). However, underlying these instances of support is the undeniable truth of disparity within the patient experience. Navigating the intricacies of the U.S. drug pricing system to secure desired treatment or advocate for change presents formidable challenges for patients. In healthcare, we've long emphasized consumer choice, evident in the multitude of health plans available to Medicare beneficiaries and the diverse benefit structures offered by different private employers. Yet, this abundance of options paradoxically complicates decision-making for patients. In essence, within a system as labyrinthine as our current drug pricing framework, it's unrealistic to expect patients to effortlessly identify and champion the changes they desire. Consequently, our opaque system fails to empower patients to fully comprehend the value of rebates or discounts associated with their medications (and so they often do not directly recognize the value of their drug’s discount or rebate).

So should we be surprised that such a system might be increasingly used by an ever-more vertically integrated drug channel for their own gain? Especially given that for the largest vertically integrated players in the drug distribution channel, they can bear the fruits of rebates and the 340B program at multiple layers of their enterprises.

Take a company like CVS Health (just for illustrative purposes). As an insurer (Aetna), a PBM (Caremark), and pharmacy (CVS), 340B can provide a cascade of profit opportunities to a publicly-traded company with none of the pesky obligations imposed on hospitals and other Covered Entities to provide care to those who otherwise can’t afford it.

Where are the market-based checks and balances when there is increasingly less of the market in competition with anyone but itself? Have you ever had an argument (think contract dispute) with yourself? Did you win the argument (with yourself)? Hmmm.

Closing Perspectives on the Value of Money From Sick People

Drug pricing is complex, subject to many potential different perspectives on the same set of facts. Given the heightened scrutiny of the 340B program (legislation, litigation, etc.), we understand that our delineation of winners and losers in such a hot-button space can be an easy path to enemy-generation. The end goal of 340B is noble, and there are many providers utilizing the program for incredible good. The end goal of health insurance is similarly noble. However, these facts should not detract from addressing the program’s deficiencies and contributions to American drug pricing absurdity.

We know that there is no panacea to the drug pricing dysfunction we see in the United States. If there were easy answers, there are enough smart people in Washington D.C. and across the country who have been studying drug pricing that any universal win-win-win scenarios would have risen to the top and been enacted (even with a government far more dysfunctional than the one we currently have).

Rather, we offer today’s report knowing full well that Humalog is not universally representative of all drug pricing experiences in this country. Even now, we know that because of the price reductions on insulin, 340B Covered Entities who relied on insulin-related revenues are facing financial challenges in 2024 that they did not face in 2023 (a function of their reliance on Money from Sick People and a funding source that is tied to over-inflated drug prices). We used Humalog for this month’s analyses because it just so happens to be the one of the few drugs with enough of the puzzle pieces on the board that we might actually start to grasp the complicated way our system seeks to rationalize drug prices while serving a bunch of often-conflicting priorities.

Ultimately, that is the issue at the heart of the matter.

It is not clear to those of us at 46brooklyn what policymakers want drug pricing to actually accomplish in this country.

Are we paying the highest rates in the world for drugs to develop ever-more innovative and novel treatments? If so, then can we really complain when costs are high? Isn’t that the point of the investments we’re making? Alternatively, are we pricing drugs such that other healthcare services can be more affordable? Drug pricing data over time seems to suggest that no price is too high to pay for drugs, so long as it is associated with a juicy enough rebate. Said differently, we might as well let drug prices go to the moon, because then doctors and hospital visits can be free through cross-subsidizing the premium off-sets of drugs against the costs of those services (and we’ll likely need more of those services if we cannot afford drugs to maintain or improve our health). Do we care to ensure a robust network of pharmacy providers to access medicines and services? Are we trying to price drugs such that we can get access to the medicines we need when we need them? Well, that almost certainly cannot be our goal when all of the levers of our system seem designed to disincentivize or otherwise financially punish the person who needs the drug that produces the rebate.

How can we ever get better in such a system that pay-walls cures behind legal bribes for access?

And so we will continue to try and study drug prices, not because it is easy, but because it requires a great deal of perspective and dialogue.

And we welcome that dialogue. It is arguably long overdue.